Need support?

Call us and get support from one of our advisors.

Call for Free 877-403-8834By 2050, hearing loss is expected to affect nearly 2.5 billion people to some degree1. That number may seem staggering, but not all hearing loss is the same, and the level of severity can vary from person to person or change over time. Let’s explore the degrees of hearing loss and their impact, plus how treatment can help.

Hearing loss doesn’t have one simple definition. In fact, there are several degrees of hearing loss, which vary based on severity. The stages of hearing loss range from mild to profound, and hearing that is impaired beyond profound levels is considered deafness.

Note: The degrees of hearing loss are different from the stages of deafness. While deafness and profound hearing loss can be used interchangeably to describe the inability to hear, an important distinction is that some individuals with profound hearing loss identify as Deaf and consider themselves part of the Deaf community. This goes to show that total hearing loss is more than just a medical condition—it can also affect how a person defines themself and affects where and how they find community with others.

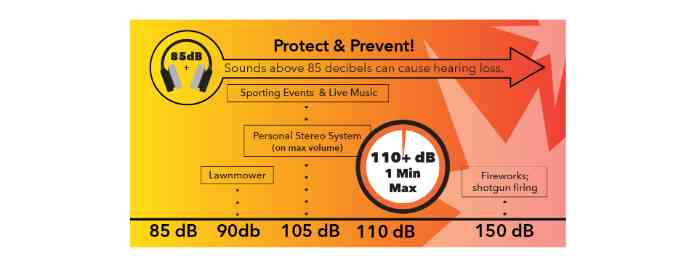

Hearing loss is measured in decibels (dB), a unit of measurement for sound levels or intensity. The degree of impairment is determined by the lowest level of decibels your ears can hear. For example: If you can’t hear sounds below 50 dB, it is considered moderate hearing loss.

Your hearing care professional may conduct a variety of tests to determine your level of hearing loss. Common hearing tests include:

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), normal hearing is defined as the ability to hear 20 dB or better in both ears1.

To learn more about hearing protection, our helpful decibel chart can help you understand when sound exposure can become dangerous.

There are several ways to classify hearing loss, but the degrees of hearing loss are commonly broken into five levels.

The following chart shows the degrees of hearing loss based on WHO guidelines2.

Degree of hearing loss — Hearing loss range (dB)

No impairment — 25 dB or better

Mild — 26-40 dB

Moderate — 41-60 dB

Severe — 61-80 dB

Profound — 81 dB or greater

This rating system is commonly used. However, other guidelines and emerging frameworks measure hearing loss differently, accounting for factors like noise levels in the surrounding environment, bilateral or unilateral hearing loss and more. One measurement that’s emerging as a simple way to understand and measure hearing loss over time is the Hearing Number Test, developed by Johns Hopkins.

As hearing loss increases, it becomes more difficult to hear and understand speech or differentiate sounds in noisy environments.

For mild hearing impairment, counseling is common and hearing aids may be recommended. In the case of moderate to profound hearing loss, it may even be difficult to hear in quiet environments and hearing aids are usually recommended2.

However, a 2019 study estimated that fewer than 10% of individuals with mild to profound hearing loss utilized a hearing aid3. The adoption of hearing aids and other treatments is critical, as hearing loss can affect more than just the ears. Research has shown that individuals with hearing loss are also at risk for:

The good news: Treatments and interventions like hearing aids can help. A 2024 study concluded that hearing aid usage was associated with significantly lower likelihoods of moderate depression compared to nonuse5. In many cases, customized therapy that accounts for socioeconomic factors is also recommended—this can significantly improve social and emotional well-being for those with hearing loss6.

If you or a loved one are noticing signs of hearing loss, don’t wait – schedule a free hearing test* at Miracle-Ear. Our licensed hearing care professionals will take the time to get to know you and your needs, offering personalized hearing aid recommendations that help you stay connected to everything that matters most in your life.

1 World Health Organization: WHO. “Deafness and Hearing Loss.” Who.int, World Health Organization: WHO, 20 Mar. 2019, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss.

2 Olusanya, Bolajoko O, et al. “Hearing Loss Grades and the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization, vol. 97, no. 10, 3 Sept. 2019, pp. 725–728, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6796665/, https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.19.230367.

3 Haile, Lydia M, et al. “Hearing Loss Prevalence, Years Lived with Disability, and Hearing Aid Use in the United States from 1990 to 2019: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study.” Ear and Hearing, 15 Sept. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1097/aud.0000000000001420.

4 Wei, Jingxuan, et al. “Association of Hearing Loss and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 15, 21 Oct. 2024, https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2024.1446262.

5 Zhang, Liansheng, et al. “Association between the Hearing Aid and Mental Health Outcomes in People with Hearing Impairment: A Case-Control Study among 28 European Countries.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 361, 1 Sept. 2024, pp. 536–545, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.06.085.

6 Yadav, Arun Kumar, et al. “Impact of Hearing Aid Usage on Emotional and Social Skills in Persons with Severe to Profound Hearing Loss.” Journal of Audiology and Otology, vol. 27, no. 1, 10 Jan. 2023, pp. 10–15, https://doi.org/10.7874/jao.2022.00290.